Holding Stocks is Hard

As I was scrolling through Twitter last week, I saw a chart that stopped my finger in its tracks. It shows the average number of years investors have held stocks for the past 90 years, according to the NYSE:

I have a few thoughts. First, trading was also really popular in the 1930s. Second, the peak holding period in the 50s and 60s was still only 8 years!? And third, people are holding onto their stocks for less and less time as the years go by. The average holding period is currently less than one year.

There are likely many reasons for the consistent drop. The main one would be transaction costs for buying and selling stocks have basically been eliminated and platforms like Robinhood make trading way more accessible than it’s ever been. I would also guess that as investing has become more mainstream, the media hasn’t done a great job of helping investors adopt a calm and patient approach to investing.

We know that stocks are a great (historically, the best) asset class for earning long-term returns. So, why is holding onto them so hard? It seems so simple. Just purchase the stock of a company you believe in and stick with it. However, the data tells us this rarely happens.

Amazon is the poster child for the classic trope of “If you would have put $10,000 into [insert wildly successful stock] at [insert specific time in the past] you would have [insert crazy amount of money] now.”

Amazon is one of the best-performing stocks ever. It’s up 340% over the last 5 years, 1,490% over the last 10, and 26,540% over the last 20.

Absolutely bonkers.

It’s easy to say now that everyone should have purchased Amazon stock 20 years ago and held the entire time until now, but it hasn’t been an easy stock to hold. The stock’s ascent has been anything but certain or inevitable.

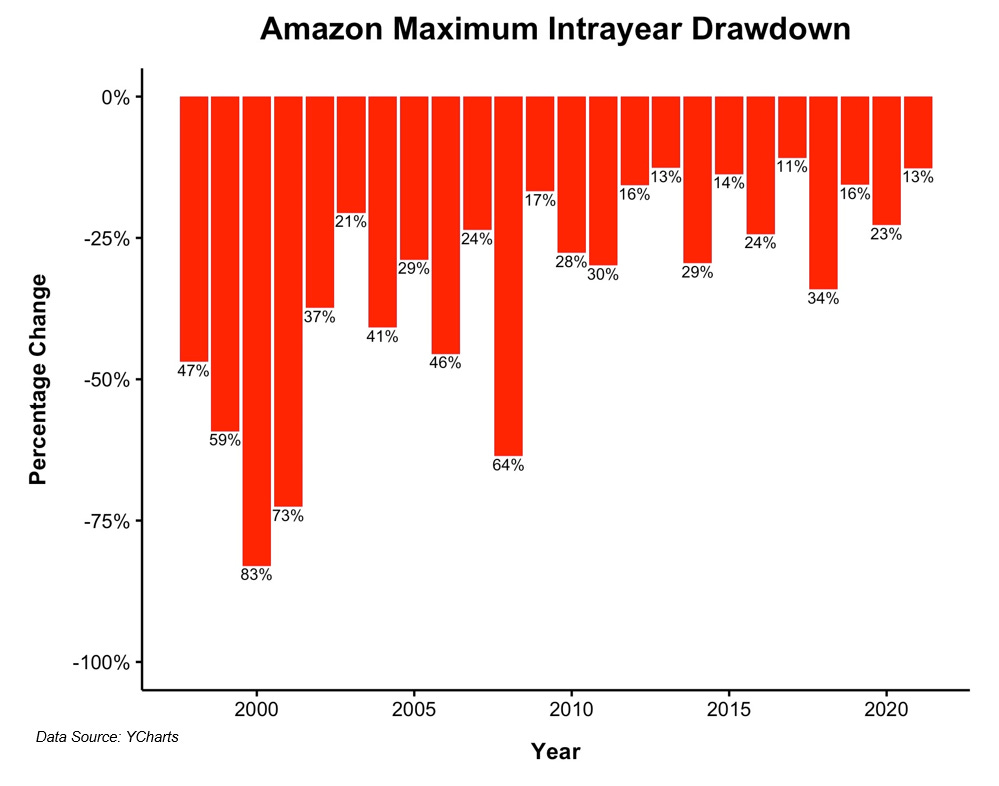

Michael Batnick recently shared an awesome chart that shows Amazon’s percentage declines each year since 1998:

The average intrayear drawdown for Amazon is 33%. It’s fallen 15% in just three days 107 different times, it’s lost 6% a day 199 times, and fell 95% from December 1999 to October 2001.

In order to get those massive returns, you would have to have had an insane amount of dedication and be void of human emotions to sit through the extreme volatility and bone-crushing losses. During those times, you would have had no idea if the stock was going to rebound. No one would have blamed you for selling.

Since 1980, more than 40% of all companies in the U.S. stock market have experienced a decline of 70% or worse without recovering. Just because you take big risks does not mean you’re entitled to big rewards.

There’s never been a stock chart that shows a consistent line moving upward. There are always ups and downs which take you on an emotional rollercoaster when you’re an owner of that stock.

Howard Marks wrote about this in a memo for Oaktree Capital a while back:

“Two of the main reasons people sell stocks is because they go up and because they go down.

When they go up, people who hold them become afraid that if they don’t sell, they’ll give back their profit, kick themselves, and be second-guessed by their bosses and clients. And when they go down, they worry that they’ll fall further.”

It’s difficult to hold stocks for a long period of time. It’s easier to do when you have an actual investment plan and are not buying and selling based on gut feelings. Emotion is the enemy of every portfolio.

Additionally, holding becomes even easier if you’re diversified. Being diversified reduces the size of the ups and downs and avoids having all of your emotions tied up in a single stock. It’s easier to hold onto the belief that an entire economy or industry will recover and continuously improve rather than hoping a specific company performs well.

Buying stocks is easy. It’s the “holding” part of a long-term investment strategy that trips people up. But of course, that’s where all of the money is made.

Thanks for reading!